Drinking sheep milk can be a real challenge for many people – particularly those ‘off a farm’.

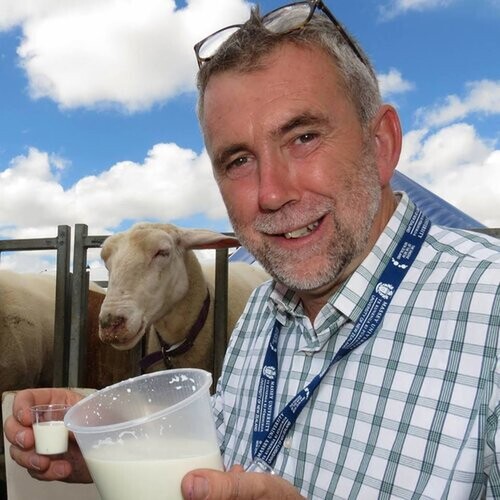

I spoke at a food futures event in Palmerston North recently and afterwards offered small servings of sheep and cow milk to those that attended. My claim is that we really don’t know an agricultural industry’s until we let it products slide over the hundreds of alert taste buds in our mouths.

While serving and chatting to tasters I noticed a woman standing back from the group - watching carefully. Her face suggested she was experiencing some kind of anguish. When the crowd thinned she came forward and told me she grew up on a sheep and beef farm in rural Wairarapa. She then looked down at the milk and paused. I asked if she’d like to try sheep milk and poured 30mls into one of the plastic shot glasses. She looked at the small glass sitting on the table. ‘No I don’t think I can!’ and stepped back.

Fonterra’s chief scientific officer, Jeremy Hill, who had also spoken at the event, came forward to taste the milks. Much to his relief he correctly identified sheep over the cow milk. We chatted about sheep milk’s chemical composition, as you do with scientists. All the while the reluctant taster watched and listened. Emboldened by Jeremy’s performance, she then came forward again. I poured another shot glass of sheep milk and offered it again. ‘Oh all right’, she said gingerly. She picked it up, raised it to her lips and held it there for a moment. ‘No I can’t, sorry’ she said. She put the small plastic glass of milk back on the table, turned and walked off, continuing to apologise.

So why was this so troubling for her? Surely someone ‘off a farm’, someone raised on the land, salt of the earth and all, would be up for such things. It’s just milk – surely! But for many, it certainly is not just milk. It might have superior nutritional, environmental and economic possibilities, but our taste buds don’t make simple biochemical decisions. Rather they come pre-organised by our early experiences and relations.

What mum and dad said and did is packed in there with the biochemical signalling. So when we bring a new food to our noses and lips, as the aromas start to coat our nostrils and food slips across our tongue, our unconscious ‘thinking’ is on full alert. As the saying goes, foods have to ’think good’ as well as ’taste good’.

If you’re 'off a (sheep) farm’ however, it’s likely the very thought of drinking the milk of sheep, is not a ‘ good thought’. It is wrapped in the experience of lambing and crutching. It comes wrapped in dags, sweat, urine and the stress of a wool shed in full flight. It’s a ‘bad thought’, as Donald Trump might say.

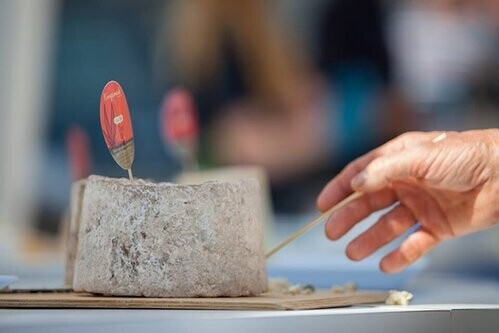

Of course some can put these rising thoughts aside when, in this case, the ‘university’ is offering something novel. Others take courage from the tasty sheep cheeses eaten on holiday or in some exotic locale. But for a few that are ‘off a farm’, 30mls of fresh sheep milk is simply an invitation to a taste bud revolution, and particularly an invitation to kiss the back end of a daggy sheep at crutching time.

It’s an invitation to break all the farm family rules about good food and good relationship. So when someone asks me why sheep dairying has previously struggled to develop as an industry in New Zealand I pour them a glass of fresh cool sheep milk and ask then to take a swig.

Craig Prichard is often described as Sheepmilk NZ’s chief networker. He is the co-organizer of the annual Sheepmilknz Conference (March 13-14, 2017) and is involved in numerous projects supporting this fledgling dairy sector. Originally from Taranaki, Craig mum’s family were South Taranaki dairy farmers and his Dad spent 50 years fixing tractors, trucks and cars for folk in Waverley, Hawera and New Plymouth. Craig teaches (and practices) organizational development and change for Massey University and is a (very) small-scale sheep dairy farmer and (very) amateur sheep milk ice cream, yoghurt and cheese maker.